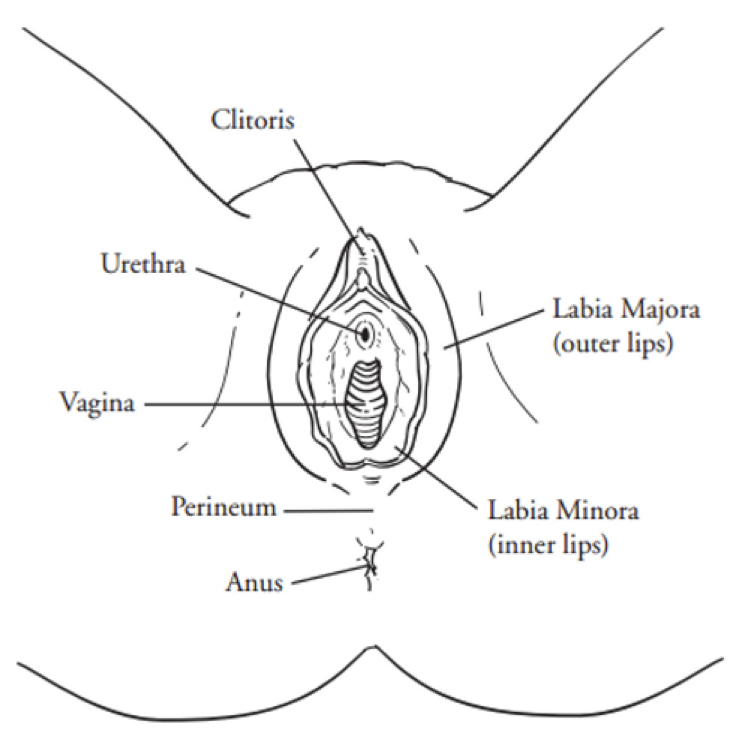

How much do you know about your anatomy? What is really considered normal? Should we even say that something is “normal?” Well with this series of blog posts, I hope to dispel some of the myths about female anatomy, as well as discuss certain changes in pelvic anatomy that would warrant a visit to your gynecologist.

As always, this post does not take the place for actual medical advice. If you have concerns or questions, please reach out to your provider. That said, to the vagina!

As always, this post does not take the place for actual medical advice. If you have concerns or questions, please reach out to your provider. That said, to the vagina!

Continuing our delve into anatomy, this blog will discuss the vagina. From the Latin word meaning “sheath,” the vagina is a tubular structure, extending from the uterine cervix to the vestibule. It averages approximately 6.2 cm in length, with a width that can vary greatly (as seen in childbirth). Much like the vestibule, its embryologic homologue is the prostatic utricle, and on a cellular level, it is composed of both rigid “parabasal” cells that give it shape and form, as well as flexible, glycogen-containing “superficial” cells that allow it to stretch and withstand trauma.

The vagina has some interesting characteristics. Hormonally speaking, it is rich in estrogen receptors of all types. Estradiol, the most potent form of estrogen, composes the majority of its receptor affinity. A decrease in this hormone, as is seen with menopause, is one of the reasons that many women experience vaginal dryness or pain with intercourse following that transition. Another interesting thing about the vagina is that many medications have a vaginal route of administration. This is because the mucosal lining of the vagina is porous, and allows for dissemination of medication through the walls, and into the bloodstream. Hormonal medications utilize this route of administration quite frequently, but antibiotics, antifungals and even anti-nausea medications will sometimes be given vaginally, as well.

As a whole, disorders that originate from the vagina itself are rare. That said, many gynecologic conditions have symptoms that manifest vaginally, such as the increased vaginal discharge that is seen with cervicitis, or the vaginal pain that often accompanies pudendal neuropathy. A thorough history and physical is often needed to determine whether the cause of the patient’s complaints is due to a problem with the vagina itself, or if the vaginal symptom is just a manifestation of extravaginal disease. What are some of those vaginal disorders? Well let’s take a look!

Some Vaginal Conditions (that actually come from the vagina)

Infectious Vaginitis

By far the most common vaginal condition (that actually comes from the vagina) is vaginitis. Vaginitis is an overarching term, simply meaning inflammation of the vagina, and while there are many different causes of vaginitis, I would like to focus on one of the most common types, bacterial vaginosis (BV). Simply speaking, BV is an overgrowth of normal bacteria within the vaginal mucosa. The most common bacteria involved are forms of Lactobacillus, but other species of bacteria, including Gardnerella, Prevotella, Fusobacterium and Bacteroides are often implicated in this condition as well.

Bacterial vaginosis is not a sexually transmitted infection, although it is often precipitated by sexual contact, and may increase the risk of developing a STI. Other factors such as changes in diet, medications, or alterations in the vaginal pH (such as with douching) can cause the development of BV as well. The hallmark symptom of BV is vaginal discharge. This discharge is often irritating to the vaginal mucosa, and can cause itching or discomfort, and may produce an amine, or “fishy,” odor.

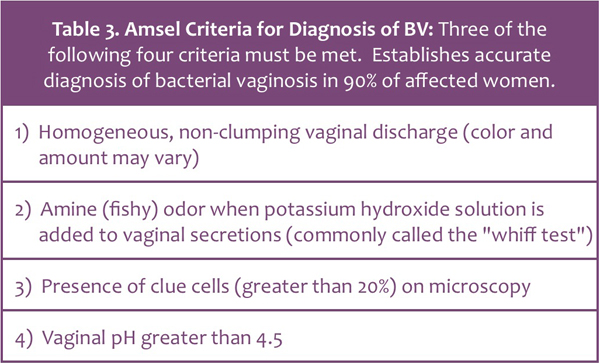

The diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is rather straightforward, and is based off of Amsel’s criteria (listed below).

Bacterial vaginosis is not a sexually transmitted infection, although it is often precipitated by sexual contact, and may increase the risk of developing a STI. Other factors such as changes in diet, medications, or alterations in the vaginal pH (such as with douching) can cause the development of BV as well. The hallmark symptom of BV is vaginal discharge. This discharge is often irritating to the vaginal mucosa, and can cause itching or discomfort, and may produce an amine, or “fishy,” odor.

The diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is rather straightforward, and is based off of Amsel’s criteria (listed below).

Treatment for uncomplicated BV is equally simple, and involves either medication to eradicate the bacterial overgrowth, or dietary/lifestyle changes to improve the vaginal pH/flora. Should these treatments fail to fully resolve symptoms, further investigation is warranted.

Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis (DIV)

On the other end of the vaginitis spectrum is an noninfectious, inflammatory disorder of the vaginal epithelium, known as desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, or DIV. DIV typically occurs in postmenopausal women, although in my personal practice, I have seen it in quite a few premenopausal patients. The hallmark symptom of DIV is a copious vaginal discharge that is very thick – almost glue-like – in its consistency. A vaginoscopic exam will reveal multiple areas of diffuse redness with yellow-tinged vaginal secretions. At times, small red macules -flat areas of irregular shape – will also be present on the vaginal wall.

Diagnosis of DIV is based off of history, symptoms, and bacterial cultures. A wet-mount preparation will reveal decreased acidity, multiple white blood cells, and none of the normal “good” bacteria. If a bacterial culture is taken, Group B Strep (which is normally not pathogenic) is often found. Treatment for DIV is focused on reducing the inflammatory aspect of the condition, changing the pH, and suppressing any bacterial activity. I typically use a compounded estradiol, clindamycin and hydrocortisone cream for this purpose, although other treatment protocols do exist.

The Take-Home

Honestly, the most important factor when it comes to treating vaginitis is correct identification. BV does not equal DIV, vaginal Crohn’s, or a Chlamydia infection, all which have vaginal discharge as a common symptom. Some practitioners may knee-jerk send in a prescription for an antibiotic when told by their staff that a concerned patient called complaining of vaginal discharge; obviously this is not best practice, and in some cases, may make the symptoms worse. It is my opinion that women with vaginal discharge – especially if it causes pain, itching or other bothersome symptoms – should be evaluated, and the discharge cultured and examined microscopically.

Well friends, that wraps it up for this blog. Next time we’ll examine the pelvic floor in the final installment of It’s All About Anatomy. Until then, have a great week, and don’t forget – there is hope, there is help, there is Haven Center!

Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis (DIV)

On the other end of the vaginitis spectrum is an noninfectious, inflammatory disorder of the vaginal epithelium, known as desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, or DIV. DIV typically occurs in postmenopausal women, although in my personal practice, I have seen it in quite a few premenopausal patients. The hallmark symptom of DIV is a copious vaginal discharge that is very thick – almost glue-like – in its consistency. A vaginoscopic exam will reveal multiple areas of diffuse redness with yellow-tinged vaginal secretions. At times, small red macules -flat areas of irregular shape – will also be present on the vaginal wall.

Diagnosis of DIV is based off of history, symptoms, and bacterial cultures. A wet-mount preparation will reveal decreased acidity, multiple white blood cells, and none of the normal “good” bacteria. If a bacterial culture is taken, Group B Strep (which is normally not pathogenic) is often found. Treatment for DIV is focused on reducing the inflammatory aspect of the condition, changing the pH, and suppressing any bacterial activity. I typically use a compounded estradiol, clindamycin and hydrocortisone cream for this purpose, although other treatment protocols do exist.

The Take-Home

Honestly, the most important factor when it comes to treating vaginitis is correct identification. BV does not equal DIV, vaginal Crohn’s, or a Chlamydia infection, all which have vaginal discharge as a common symptom. Some practitioners may knee-jerk send in a prescription for an antibiotic when told by their staff that a concerned patient called complaining of vaginal discharge; obviously this is not best practice, and in some cases, may make the symptoms worse. It is my opinion that women with vaginal discharge – especially if it causes pain, itching or other bothersome symptoms – should be evaluated, and the discharge cultured and examined microscopically.

Well friends, that wraps it up for this blog. Next time we’ll examine the pelvic floor in the final installment of It’s All About Anatomy. Until then, have a great week, and don’t forget – there is hope, there is help, there is Haven Center!