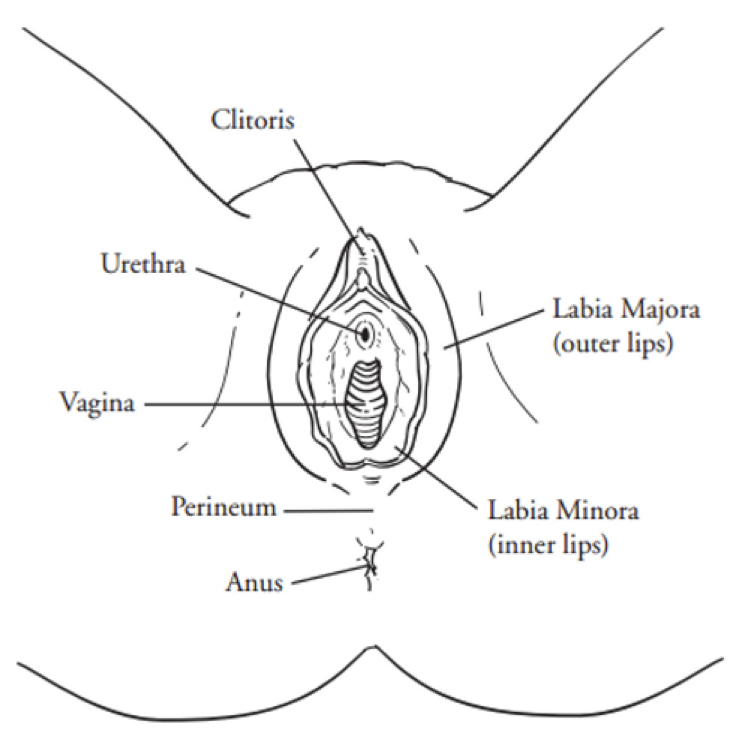

How much do you know about your anatomy? What is really considered normal? Should we even say that something is “normal?” Well with this series of blog posts, I hope to dispel some of the myths about female anatomy, as well as discuss certain changes in pelvic anatomy that would warrant a visit to your gynecologist.

As always, this post does not take the place for actual medical advice. If you have concerns or questions, please reach out to your provider. That said, to the Pelvis!

For the final blog in our anatomy series, I thought I would focus on a pelvic structure that is so very important to sexual health, but also affects urination, defecation, and overall core and low back support. It is with great joy that I present to you…

The Pelvic Floor

The Pelvic floor is a fascinating group of muscles that form a hammock for your pelvic organs, keeping them in correct anatomic position. Found in both men and women, the pelvic floor is important in sexual function, defecation, movement (through its attachments to the hips and legs), and controlling urination. In women, the pelvic floor allows for the pelvic bones to move during childbirth, and is one of the reasons women are able to deliver vaginally. I should note that most practitioners use the terms pelvic floor and pelvic diaphragm interchangeably, although there is an anatomic difference between the two.

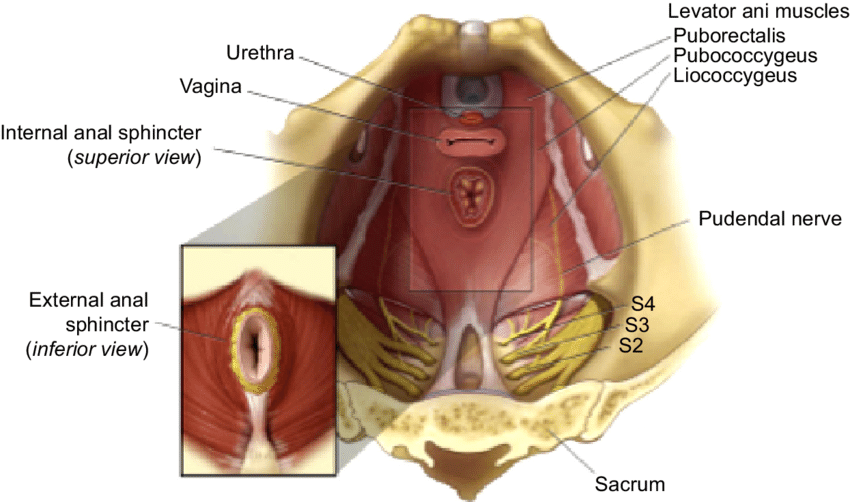

Musculature

The Pelvic floor is anatomically comprised of two distinct muscle sets, the Levator Ani group (pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and puborectalis), and the Coccygeus. In addition, the Obturator internus (which on that diagram above is the white, filmy muscles adjacent to the iliococcygeus), plays a substantial part in pelvic function, too. These muscles work in tandem to aid in all sorts of ambulation and bodily functions, relaxing and contracting as needed depending on the desired action. Like all muscles, they can be damaged, usually during events that cause substantial stretch trauma (such as childbirth), although repetitive stress to the muscles (such as with chronic cough) can cause injury over time, too. In addition, atrophy to the musculature can occur in patients with neurologic conditions, or in very sedentary individuals.

Innervation

The innervation (nerve supply) to the pelvic floor originates mainly from the sacrum. Sacral nerves 2,3, and 4 form the pudendal nerve, which in turn descends through the pelvic floor, exiting through Alcock’s canal in the groin. It then branches into a clitoral branch, a perineal branch, and an anal branch, innervating those respective structures. Damage to the pudendal nerve typically occurs at the nerve root (in the sacrum), or where it traverses the pelvic floor. In both cases, trauma is often the cause of the nerve damage, be it from something like a fall, car wreck, or vaginal delivery. In addition, muscles spasms along the pelvic floor can entrap the pudendal nerve, which causes sharp, stinging pain in structures downstream from the entrapment.

Treatment for pudendal nerve issues is tricky, and often involves multiple therapeutic modalities. Medication, nerve blocks, physical therapy, and behavioral therapy often work hand-in-hand, and with good care, significant improvement or resolution of symptoms can be achieved. Rarely is surgery indicated for pudendal nerve dysfunction.

Vasculature

The anterior division of the internal iliac artery provides the majority of the blood supply to the pelvic floor. That vessel has three “terminal” branches, the pudendal artery, the inferior gluteal artery, and the inferior vesicle artery, all of which distribute blood to various structures in the pelvis.

As with nerves, damage to, or entrapment of, blood vessels cause downstream effects. If a vessels is mildly compromised, the muscles that it supplies will experience “ischemia,” or a decrease in oxygenate blood. This manifests as pain – often dull, or achy in quality. Peripheral blood vessels often try and compensate for this decreased blood flow by bringing more blood to the area, thus creating a reddened or “hyperemic” appearance. This explains why patients with vestibular pain secondary to pelvic floor spasms often have a very red, irritated looking vestibule.

Treatment for vascular-relate pelvic floor disorders is based around restore normal blood flow. This can be accomplished by medications (blood thinners, antihypertensives, etc), physical therapy, or even surgery, especially if congenital malformations that affect the shape and flow of the pelvic vessels are present.

Prolapse

I would be completely remiss if I did not talk about pelvic organ prolapse in a blog concerning the pelvic floor. Pelvic organ prolapse is a condition in which the pelvic organs lay in an altered anatomic position secondary to deficiencies in support. There are four main types of pelvic organ prolapse: cystocele, rectocele, uterine prolapse, and vaginal vault prolapse. As each of these conditions warrants a blog itself, I’ll just go over the basics of each type.

A bladder prolapse, or “cystocele,” is a condition in which the bladder falls into the anterior, or top, portion of the vagina and can protrude out of the vagina with increased intra-abdominal pressure (such as coughing or laughing). Symptoms of bladder prolapse include urinary incontinence, urinary hesitancy, or sensation of fullness in the pelvis.

A “rectocele”, or posterior vaginal wall prolapse, is a condition in which the support structures on the posterior aspect of the vagina are weakened, and the rectum is allowed to protrude into the vaginal canal. This can cause a sensation of pelvic fullness, and may lead to constipation. Some women may have to place a finger inside the vagina and help push stool, in a maneuver known as “splinting.”

A uterine prolapse is a condition in which the support structures of the uterus have weakened, causing the uterus to “fall” into the vagina. This typically manifests as low back pain and pelvic pressure, and in some women can cause pain with intercourse or even bowel or bladder problems.

Finally, a vaginal vault prolapse is a condition that occurs after a hysterectomy, in which the apex of the vagina falls from its original position due to a loss of suspensory structures. Typical symptoms of a vaginal vault prolapse are the sensation of heaviness or fullness in the pelvis, as well as a visible bulge at the opening of the vagina.

The Take-Home

Pelvic floor health is so incredibly important. In fact, you could say that pelvic floor health = gynecologic health, at least in terms of pelvic pain, continence, and sexual functioning. If the pelvic floor is not functioning properly, a thorough pelvic floor evaluation needs to be performed. At Haven Center, we do a pelvic floor exam utilizing a bimanual vaginal technique in which we palpate the individual muscle groups, as well as perform a visual inspection to check for prolapse. Should we find an area of concern, the next step in the treatment for these conditions is a referral to a certified pelvic floor physical therapist.

Well friends, this is the end of this blog series. I hope you’ve found it informative, and have a better appreciation for gynecologic anatomy! If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to ask, otherwise I’ll see you with the next blog! Remember – there is hope, there is help, there is Haven Center!